I wanted to eat the air. I think that's a first for me.

Searching for “Our Babe”: Halifax’s Fairlawn Cemetery and the Mystery of the Titanic’s “Unknown Child,” Part II

Did you miss the first part of this post? You can catch up here.

“David could wear those”

As part of its “Disaster at Sea” exhibit, Halifax’s Maritime Museum of the Atlantic has a small, but very well-designed, section dedicated to the Titanic. The exhibit features the expected range of personal stories, passenger effects, artifacts from the ship, and emphasis on the class distinctions that played so large a role in determining who would live and who would die. One large wall panel features a reproduction photograph of the ship’s promenade deck, complete with recreated wicker deck chair. And hanging near it, a small glass case displaying a piece of wicker caning salvaged by a member of the Mackay-Bennett’s crew.

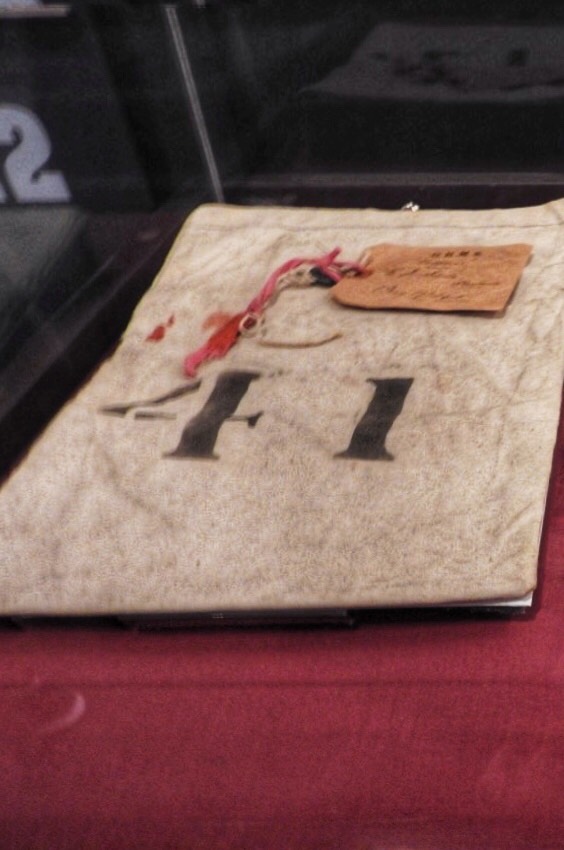

This canvas bag held the personal effects of crew member Edmund Stone, the forty-first body recovered by the Mackay-Bennett. Stone was among those buried at sea (his widow was told this was due to the condition of his remains, but the initial shortage of embalming supplies may have been the reason).

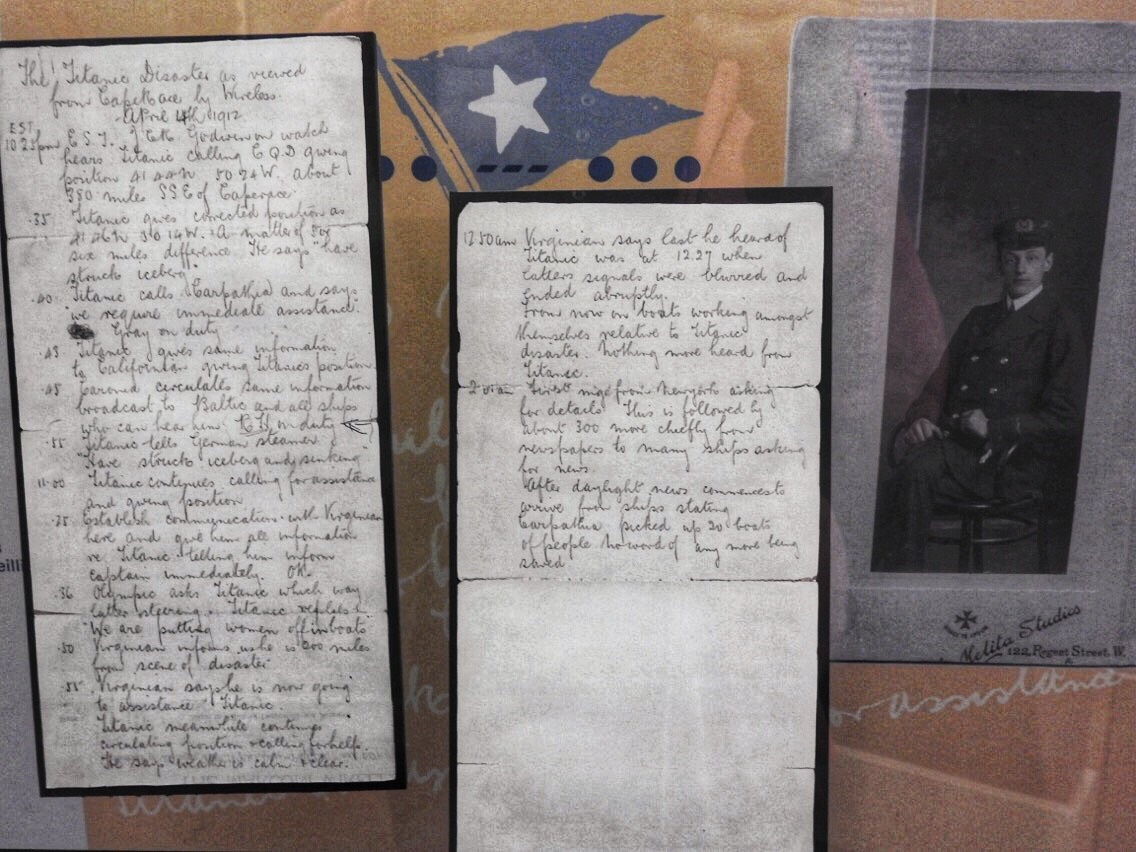

A display case the the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic containing a write-up of the various wireless messages the Marconi station at Cape Race, Newfoundland, received from the Titanic on April 14th/15th 1912. Note that the last communications were received around 2:00 am, twenty minutes before the ship went down.

[By the way, the entire “Disaster at Sea” exhibit is well worth your time. Among the (many) interesting things I picked up was that the White Star Line had a really poor safety record. The Titanic was not its first high-profile disaster. But the line’s directors seem to have been very calm about this–another maddening element of the largely avoidable tragedy of the Titanic.]

From the museum’s “Disaster at Sea” display: The S.S. Atlantic was another White Star liner. It went down off the coast of Halifax in 1873, with nearly four hundred lives lost. The wreck seems to have been the immediate fault of the officers, who had failed to take numerous precautions and did not realize they were miles off course, but a Canadian government inquiry laid the ultimate blame at the feet of the captain (who was asleep at the time of the collision), saying he displayed a lack of leadership necessary to one in so responsible a position. The White Star line suffered two further high profile losses before the 1912 Titanic disaster.

One of the last cases displays personal objects that either belonged to survivors or were recovered from the wreck site. And there they were, placed for maximum emotional impact: the little brown shoes.

I don’t choke up easily at this kind of thing. Perhaps, being an historian and well-versed in the tragedies of the past, my emotions are a little numb to its relics. Perhaps I am cynical about the methods curators and storytellers (to say nothing of, um, historians and bloggers….) use to grab and hold people’s attention. Whatever the case, I was really more excited to see something new about the Titanic than emotionally affected by the sight.

But the exhibit wasn’t finished with me yet. Standing near me, peering intently at the case, was a little boy. He was probably about five and was standing on his tiptoes, while his mother bent down to point out the various artifacts to him. When she gestured to the shoes, she said, “see, those belonged to a little boy. It says he wasn’t even two years old.” Her son looked at her and said, “David could wear those,” before turning back toward the glass. I don’t know if David is a sibling, playmate, or imaginary friend, but the little boy’s tone, somewhere between worry and wonder, was unmistakable. Also unmistakable? The way the woman tightened her grip on the boy’s shoulders after his comment. I admit this exchange cut through whatever numbness or cynicism I had been feeling before. Maybe that’s why I forgot to get a picture of the shoes.

“That little boy had a name”

Over the years, interest in the unknown little boy has ebbed and flowed, picking up whenever a major anniversary of the disaster passed or a discovery (or hit Hollywood movie) pushed the Titanic back into the news. But no progress was made in identifying him, beyond narrowing the list to the blond, male, toddlers who had been among the lost.

Nevertheless, as early as the 1920s, a firm tradition emerged, associating the unclaimed boy with two-year-old Gösta Pålsson. Little Gösta, who died along with his mother and three siblings, did fit the description, but as Judith Geller points out in her 1998 book Titanic: Women and Children First, that is all the solid evidence there is.

The rest of the story seems to have been built on sentimentalized press accounts. The remains of Gösta’s mother, Alma Pålsson, were recovered. By chance, she is buried at Fairlawn quite near to the grave of the unknown baby. A survivor had testified that he’d seen Alma’s baby swept overboard in the final moments before the ship went down. Geller suggests that the entire tradition rested on a shaken public’s desire to believe that this tragic mother and child had, in a comforting coincidence, at least been reunited after death.

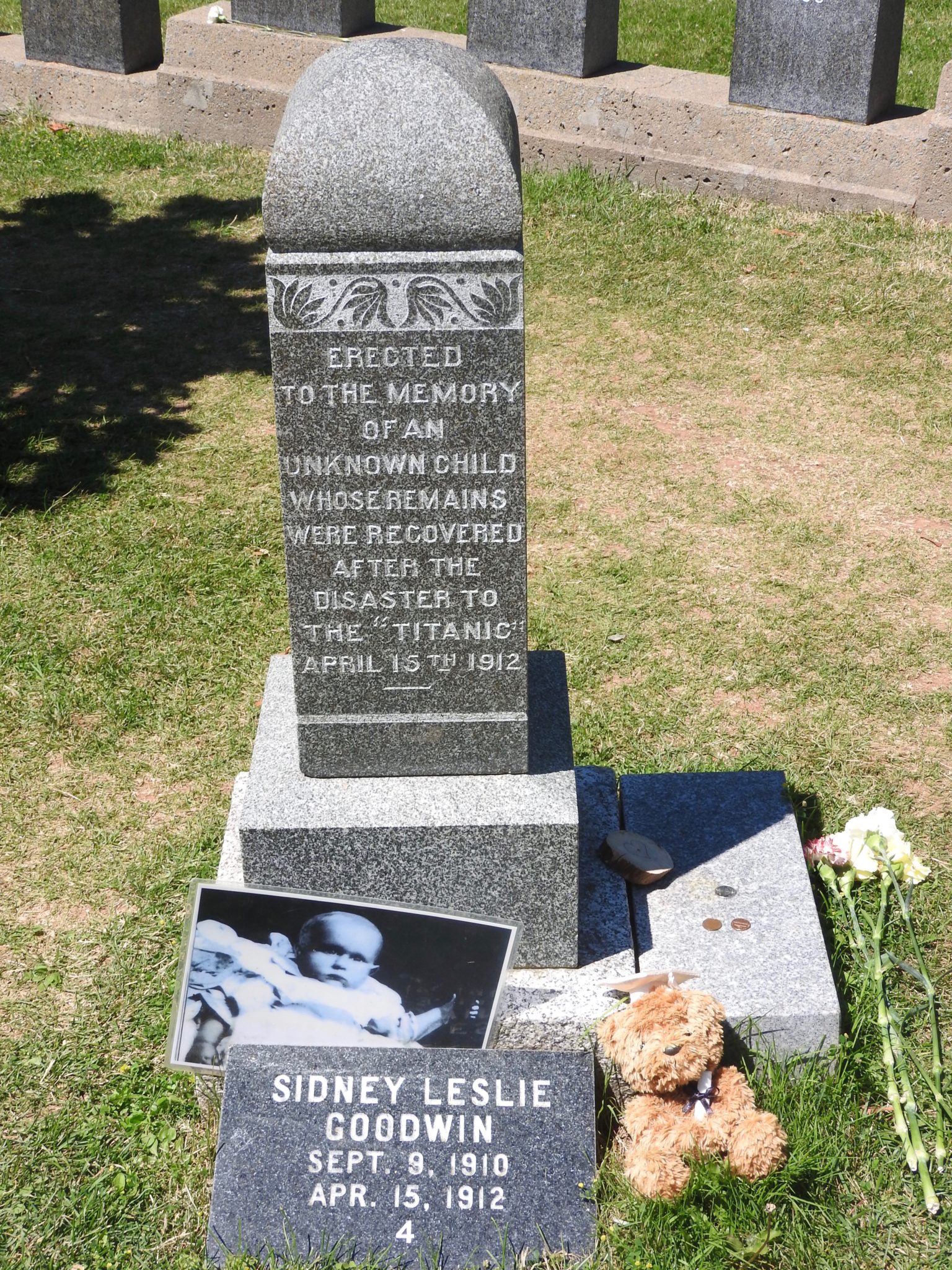

The grave of the unknown child and, in the background, that of Swedish passenger Alma Pålsson, at Fairlawn Cemetery in Halifax. Titanic lore long associated the unknown child with Alma’s youngest child, two-year-old Gösta, though it seems there was never any solid proof for this.

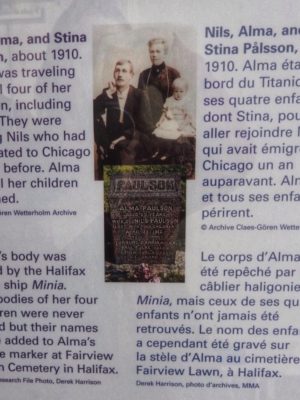

A panel at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic showing Alma Pålsson, her husband, Nils, and their daughter Stina, around 1910. Alma and all four children died in the sinking. Nils had emigrated to the U.S. about two years earlier and managed to save up enough money for his family to join him.

But science, as it has frequently over the last generation, was about to lend the historians a helping hand. The improvement of DNA technology raised new possibilities for all kinds of “cold cases,” and in 2001, a team of researchers exhumed three graves from Fairlawn Cemetery, including that of the little boy. Interestingly, the strength of the Pålsson tradition was such that the researchers either chose or were required to contact distant Pålsson relatives to obtain permission.

After nearly nine decades, the remains of all three victims were much decomposed, but researchers were able to recover an arm bone and three teeth from the baby’s grave. Between the fragile state of the samples and the time-consuming task of tracking down maternal relatives of Gösta’s (mitochondrial DNA, which is passed unchanged from mother to child, is often used for identification in cases where the use of nuclear DNA–inherited from both parents–is impossible or impractical), the tests took a while. It wasn’t until the spring of 2002 that the results came in, and they were disappointing. The unknown child was not Gösta Pålsson after all.

But having already disturbed the little boy’s grave, researchers were not about to give up. Further analysis narrowed the possibilities down to a Finnish thirteen-month-old, Eino Panula, and an English nineteenth-month-old, Sidney Goodwin. Inconveniently, the first round of tests showed that the area of mitochondrial DNA the scientists had tested for actually matched both boys–indicating a common maternal ancestor at some point in the last 2,000 years. Rather than test the second area, the team decided to fall back the original analysis of the teeth, which indicated a child closer in age to one year than two. Put together, the case for Eino Panula looked good and the team happily made an announcement to the press.

I’m unclear on what happened next. Every article I’ve looked up tells the story differently, but evidently something about the results didn’t sit right with the research team. Maybe the degraded state of the remains caused doubts. Maybe it was the DNA test that showed both boys to be a match. Maybe, as some articles have stated, they got wind of the baby shoes–newly on display in Halifax–which seemed awfully big for a thirteenth-month-old. But I think it was simply the advent of better and more sophisticated DNA testing. As technology improved, and the possibility grew that more answers could be wrung from the remains, I’m guessing the research team couldn’t resist the possibility of settling the matter once and for all. And so they tested the second area (which is more stable and less mutation-likely) of the mitochondrial DNA, and this time, the results pointed to Sidney Goodwin.

Sidney Goodwin around 1911 {Wikimedia Commons}, and, right, the rest of the Goodwin family, around 1910 {Wikimedia Commons}. The entire family was lost in the sinking, but only Sidney’s body was recovered.

Meanwhile, experts at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic had been performing some tests of their own. Though delighted by the Northover family’s donation of the leather baby shoes, museums cannot just accept on faith the backstory of any artifact that comes their way. There was no particular reason to doubt the Northovers’ story, but ninety years is a long time. Family stories, and the heirlooms that can accompany them, turn easily into multi-generational games of “Telephone,” in which each generation, however unwittingly, is increasingly likely to pass on tainted information to the next.

Calling on material culture experts, the museum determined that the shoes were likely of English manufacture and dated from between 1900 and 1925–another point in Sidney’s “favor.”

The ornery historian in me feels compelled to point out that little Eino–who had traveled to England en route to boarding the Titanic–could have acquired English-made shoes. But certainly the size of the shoes plus the DNA evidence plus the fact that the other baby in question was actually English, add up to a reasonably compelling case. The museum happily endorsed the results and got to work revising their Titanic exhibit. Today, a reproduction photograph of little Sidney Goodwin sits in the display case alongside the leather shoes.

Visiting the “Titanic graves”

Getting to Fairlawn Cemetery from Halifax’s downtown is an easy and fairly inexpensive taxi ride. It took about 15 minutes and came to roughly $16 (Canadian). I suggest you ask the driver to wait or, if you want to stay a while, get the taxi company’s number or call Lyft or Uber. Walking back downtown isn’t difficult, but it takes over an hour and isn’t very scenic.

Getting to Fairlawn Cemetery from downtown Halifax is a piece of cake, and once you’re there, the grave site is well-marked. If you taxi up there, your driver will also almost certainly be able to point you in the right direction.

The Titanic section occupies a sizable plot on gently sloping hill. There are some substantial headstones, but most of the graves are marked with simple granite stones, engraved with the date of death–April 15th, 1912–and the number assigned to each body. Space was deliberately left to add the victim’s name, should it ever be discovered, but very few have been.

Jenny Louisa Henriksson was one of the few victims identified after burial. A closer reading of the notes taken by the Mackay-Bennett crew revealed that her initials had been sewed inside a piece of her clothing.

The “unknown child’s” grave now has a small plaque at the base finally identifying the victim as Sidney Goodwin. As far as I know, there has been no movement to add his name to the original headstone. Likely that would be considered both impractical (there’s not much space left) and contrary to the way the grave has long stood for all of the Titanic’s young victims.

Fairlawn has the largest number of Titanic graves, followed by nineteen at the Roman Catholic Mount Olivet and ten at the Jewish Baron de Hirsch cemeteries. Among those buried at Mount Olivet is Margaret Rice, the mother of Eugene Rice, one of the five toddlers originally considered “candidates” to be the unknown child. Of the ten men buried at Baron de Hirsch, only two were identified. Though not noted on any of the careful descriptions of the bodies (which you can read for yourself on the very detailed “Encyclopedia Titanica” site), the other eight men must have been circumcised. I can’t think of what else the authorities would have had on which to base their assumptions. Though why at least an allusion to that wasn’t included in the descriptions, I have no idea.

The various “Visit Halifax” and “Visit Nova Scotia” booklets and websites all take pains to emphasize that the cemeteries are not tourist attractions, but rather places of solemn remembrance and respect. Given the number of tour companies that make hay of the Titanic disaster and include the cemeteries on their routes (not to mention playing up the dubious J. Dawson/Leonardo DiCaprio story), that strikes me as a rather slippery distinction. But I didn’t see any behavior that struck me as disrespectful. People (including yours truly) took photos, but I didn’t notice any selfies, and most people just walked quietly from stone to stone. Nor did I see anybody causally perched on a gravestone while listening to their guide or texting, something that I do see a lot and that is a major pet peeve of mine.

Mount Olivet is open to the public, but Baron de Hirsch, which is affiliated with Halifax’s Beth Israel synagogue, seems to be open only by appointment. Unfortunately, the cemetery’s website is vague and out of date. For more information, I’d contact the synagogue directly. Neither cemetery is far from Fairlawn, and both can be reached by taxi.

What do you think? What historical mysteries would you like DNA solve? Does finally knowing the name of the unknown child justify disturbing his grave after so many years? Have you visited any of the Titanic graves? And should a cemetery be a tourist attraction anyway? Let me know in the comments section!

I’m generally kind of “meh” on the idea of using DNA to solve historical mysteries–not sure why. Maybe I just don’t like the idea of scientists being able to do things that historians can’t! But I think this is a nice example of the way that something like DNA testing can supplement other historical evidence.

Ha, fair enough! Though I like to think of it as historians helping out the scientists by pointing them toward mysteries they otherwise wouldn’t know about!

I do get easily emotional with things regarding the Titanic – there’s a museum in Southampton, which has a lot of information on the Titanic, and they have a video just replaying over and over on a wall of people’s shoes and items falling down in the sea. Really brings it home. As for DNA testing, I’m all for it – I think that anything we can do to help solve the puzzle helps us learn, and also gives vital information for those studying general history as well as their own family history. Thanks for this really interesting post.