Did you miss the first part of this post? You can catch up here.

Up for a light and tasty historical romp? I’ve got the museum for you.

Like chocolate? Like history? Like funny statues and very low-key museums? If so, Barcelona’s Museu de Xocolata (Chocolate Museum) is for you.

The location is appropriate, as Barcelona is the city where Europeans were first introduced to chocolate. It was also the city, some 200+ years later, where the mass production of chocolate first took place. (Add this to the many reasons to like Barcelona...)

These are the first two chocolate sculptures visitors encounter and they set the tone–lighthearted more than educational–for the whole exhibit. The reason for the Barcelona footballer is obvious, but I guess the white chocolate ape munching on cocoa leaves is there to make the point that cocoa has always been popular.

The Sacred and the Profane: From “drink of the gods” to “will you be my valentine?”

For better or for worse, it is difficult to deny that the encounter between the peoples of the Americas and the peoples of Afro-Eurasia, set into motion by Christopher Columbus’ stumbling upon the Caribbean islands, is one of the most significant events of the last several thousand years. And chocolate is an excellent example of cultural exchange (not to mention a happier one than, say, smallpox, or measles, or syphilis).

If you need your faith in humanity renewed, consider that chocolate has been prized by human beings for at least two thousand years. Cultivation appears to have started with the Mayans, who called it the “drink of the gods.” Despite this exalted title, all ranks of society enjoyed chocolate–which might mean that it was consumed only on special occasions.

The Aztecs conquered their Mayan neighbors around the start of the 15th century. Like many conquerors, they found plenty to admire in the culture of the people they had subjugated, tweaking whatever was necessary to accommodate desirable Mayan practices to Aztec norms. And they took a particular liking to chocolate.

Like the Mayans, the Aztecs consumed chocolate in liquid form (indeed, it was not powdered and produced in hard form, as we are accustomed to, until the 19th century), but it seems to have been reserved for the elite or for purely ceremonial occasions. According to some historians, when captives chosen for (live) sacrifice proved too melancholy to participate in ritual dances ahead of their own executions, their Aztec captors would ply them with chocolate to provide the necessary energy boost.

Chocolate lover though I am, I do not think I would consider this adequate recompense, especially since the Aztecs drank their chocolate either in its purest, bitter form, or flavored with ground chili peppers; neither recipe would reconcile me to such a dismal fate. As for ordinary (not-about-to-be-sacrificed) women, they wouldn’t have had the opportunity to taste it at all. Aztec rulers, fearing chocolate’s stimulating effect, forbade women from drinking it.

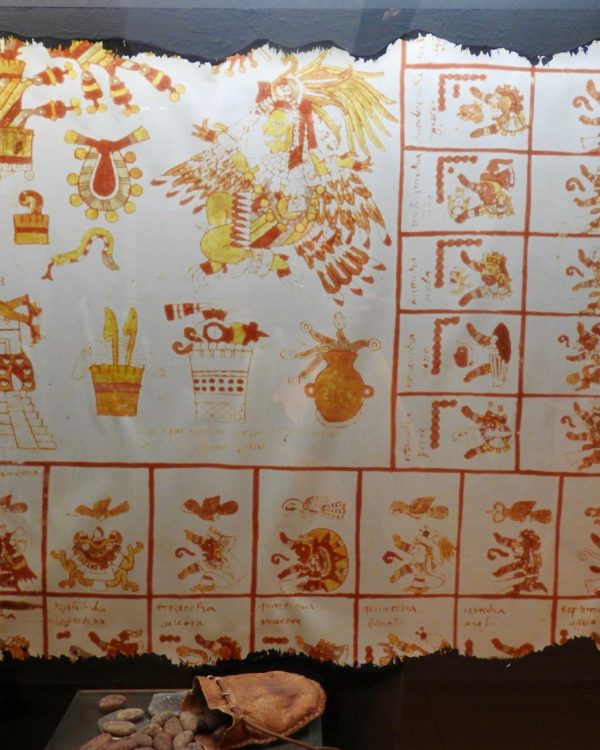

No explanatory text accompanies this reproduction, but based on its placement within the exhibit and Aztec codices that I’ve seen, I’m guessing it’s an Aztec scene–painted either before or shortly after the Spanish conquest–depicting the use of cocoa beans as currency. The Aztecs prized chocolate so highly that they extracted their taxes from their Mayan subjects in the form of cocoa beans, probably as many as hundreds of thousands of beans each year. Cocoa beans also seem to have functioned as black market currency.

Even Aztec men, including the emperor, consumed chocolate–or offered it to outsiders–only on special occasions. According to the Aztec Codices, compiled by Aztec artists several decades after the Spanish conquest, Aztec leaders had been warned of the coming of a divine individual or force. In the early 1500s, when Hernan Cortes and his fellow conquistadors arrived in what is now Mexico City, the Aztecs initially took them for that prophesied divine force and treated them according–which meant offering them chocolate. But at least one of Cortes’ soldiers, either oblivious or indifferent to the honor being done him, recorded that the drink was “disgusting.”

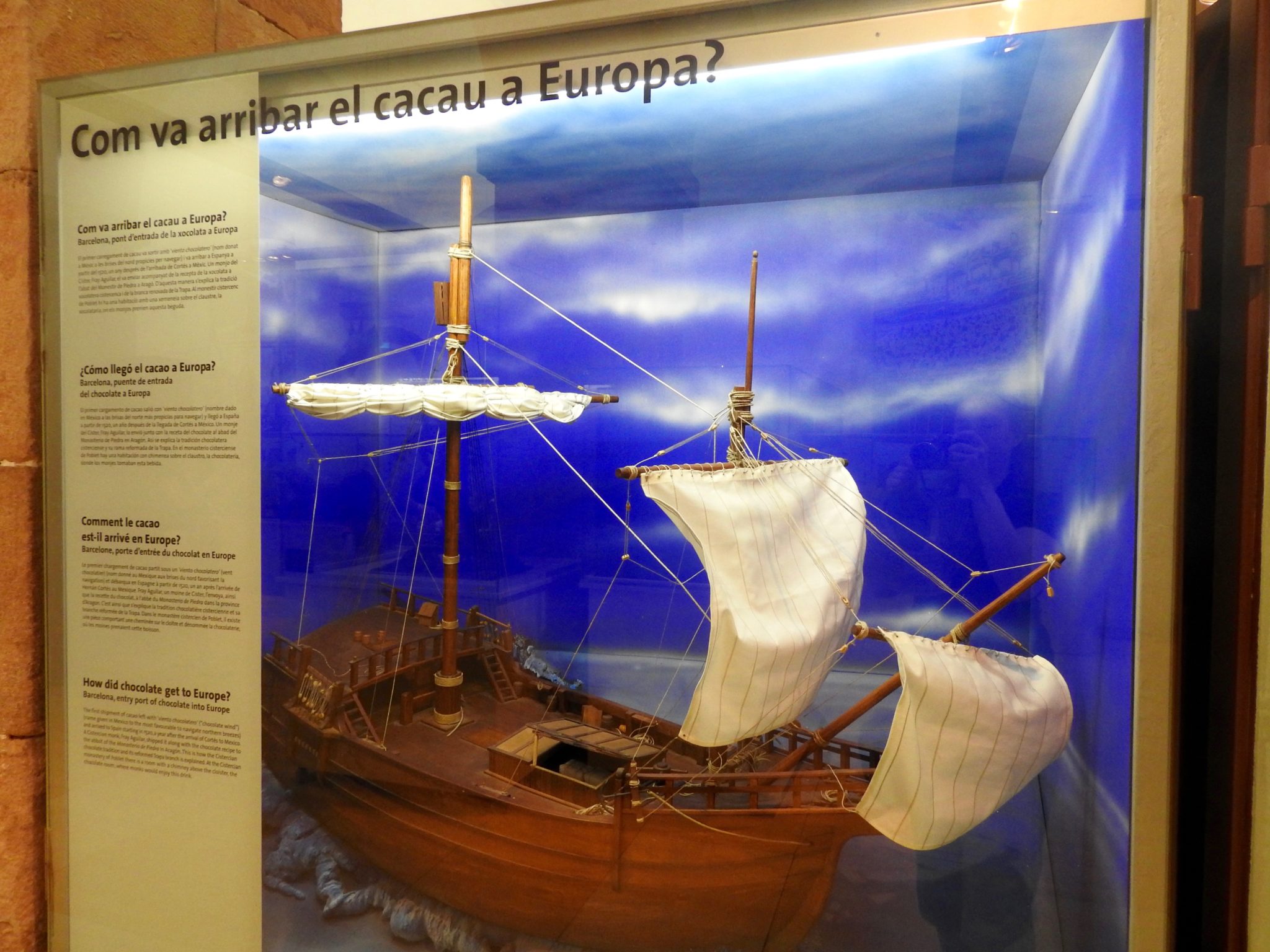

A child-friendly explanation–in four languages–of how chocolate came to Europe.

If the Aztec version was too bitter for the Spanish palate, Spaniards soon found a way around that. As truly global trade took off and Spain grew increasingly rich, luxury items like sugar, vanilla, and cinnamon were added to basic chocolate. Before long, chocolate, usually consumed in thick, creamy form, was all the rage amongst the European ruling class.

One reason for chocolate’s rapid popularity (at least initially, before Europeans had perfected the taste to suit their palates) was that the Catholic church included it on the list of liquids–along with water, tea, and coffee–permitted on fast days. Chocolate, of course, has a much higher caloric value than any of those other drinks, something that surely made it especially attractive in heavily-Catholic southern Europe. Not that the Protestant north would be left behind; hot chocolate caught on quickly in places like England and the Netherlands where it fit in well with the growing coffeehouse culture.

Reproduction prints like these, with porcelain cups and saucers placed in front of them, show the growing popularity of chocolate-drinking in Europe, while the cups and saucers, one set plain and one ornately decorated, illustrate the extent to which chocolate-drinking, eventually, became a cross-class phenomenon.

Eventually, specially-designed carafes and cups, as well as carefully-outlined drinking rituals, grew up around the drinking of chocolate. In the 18th century, as the price of chocolate fell, chocolate drinking and its attendant rituals became popular among the bourgeoisie as well. The working class, for the most part, would have to wait until the 19th century for the mass production of chocolate, to take part in the fun.

Chocolate (sculptures) everywhere……

Saint George (the dragon-slayer) is Barcelona’s patron saint and known in Catalan as Sant Jordi. This chocolate sculpture of his fearsome opponent was one of my favorites.

Don’t make the mistake of confusing the Museu de Xocolata with a stuffy (or even especially informative) history museum. The exhibits, which are quite limited, provide an interesting, but generally superficial, overview of the history of chocolate consumption. Most of the attention is on the general history of chocolate in the western world, with some extra details about its history in Barcelona tossed in for good measure. It’s quite interesting, and I have no reason to doubt any of its veracity, just keep in mind that it’s a light-hearted, kid-friendly romp, with treats at the end, not a serious history lesson.

A victorious Sant Jordi carrying off the fair damsel after slaying the terrifying dragon. I didn’t like this sculpture nearly as much, but I thought I should include it for the sake of closure (also, sorry for the bad lighting. One side of the museum was noticeably darker than the other and my photos of the second set of sculptures suffered accordingly).

Not that I’m complaining. I spent a thoroughly entertaining 45 minutes wandering through this not-hugely-historical museum (also posing with a chocolate Komodo dragon, as can be seen in the top photo; this is the closest I ever want to be to a Komodo dragon of any kind). Armed with a ticket (actually a very small chocolate bar that confers a discount at the museum cafe), visitors pass through a turnstile into a modern and airy hall. Well-designed descriptions abound, but the real star (or rater, stars) of the show are the 20 or so chocolate sculptures–depicting everything from Barcelona landmarks like La Sagrada Familia to scenes from Don Quixote and the Asterix comics, to the Smurfs (by the way, the Smurfs, I am learning, are really big in Spain).

Scenes from Asterix and Bambi, one with flash, one without, both kinda lousy…

Technological advances allowed the mass production and exportation of chocolate. These machines came from a nearby factory (I think! The only description of these pieces was in Catalan!). Mass production, combined with growth in advertising and other forms of mass culture, led to chocolate being associated, by the early 20th century, with romance and holidays such as Valentine’s Day.

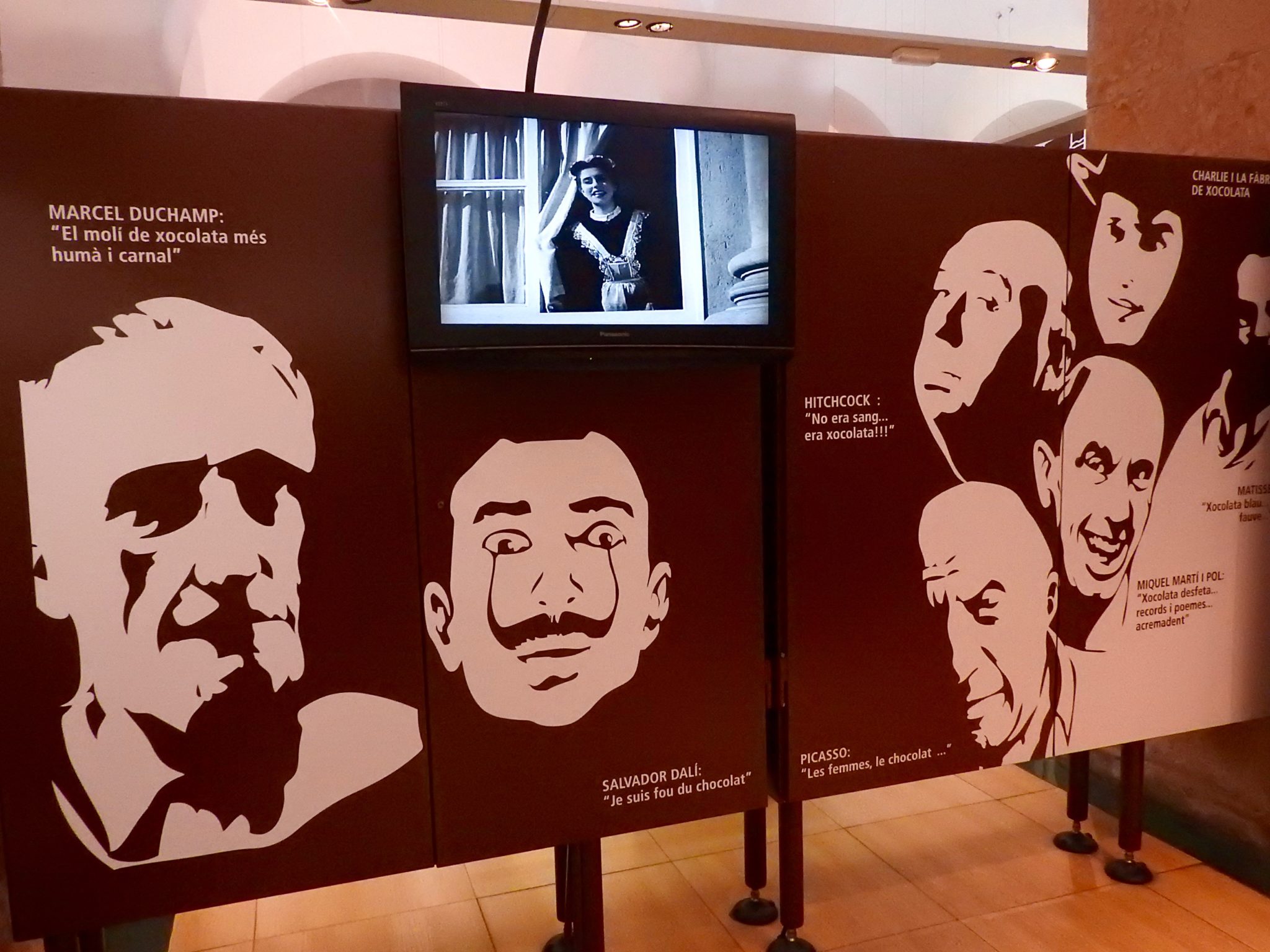

In case the chocolate sculptures and scent of chocolate wafting through the air leave you somehow unconvinced (or you are one of those curious, troubled souls who don’t like chocolate), the museum includes quotations from famous Spaniards, such as Picasso and Dalí, testifying to their love of chocolate.

A collection of early 20th century chocolate advertisements. Like many other brands, chocolate companies often made use of racial stereotypes in marketing their products. Many of these have long since disappeared, but many others can still be found throughout Europe, for products such as coffee and liqueurs.

Toward the end of the hall, there is an exhibit detailing the history of chocolate sculpture-making in Catalonia. This part is only in Catalan, but from what I could follow, it seems that the Catalans were pioneers in the art of chocolate sculpture-making (if you’re really interested, there’s a short book on the subject, available in English, in the gift shop as well).

In keeping with its focus on the experience of chocolate and not the history of chocolate, the museum offers little else in the way of solid information. The gift shop (which is really a chocolate cafe with a couple of mugs and aprons for sale) is long on yumminess and short on education; other than the aforementioned booklet on the history of chocolate sculpture-making in Catalonia, there is no real history on offer. (But if you’re interested in learning more, Sophie and Michael Coe’s The True History of Chocolate, Carol Off’s Bitter Chocolate: Anatomy of an Industry, and Sarah Moss’ Chocolate: A Global History, are well-reviewed.)

Having virtually no books with which to distract myself in the gift shop, I was forced to focus on the chocolate goods for sale. I am pleased to report that I was good, and confined myself to a small piece of white chocolate, a tiny (but rich!) truffle, and a fantastic, but intense, cup of thick hot chocolate. Though meant to be drunk and, presumably, to be reminiscent of the thick chocolate drink popular in the early modern era, this chocolate very much resembles the chocolate that comes with churros, and not the thin, watery, stuff we typically drink in North America. (In case you’re wondering, churros, much to my surprise, were not on the menu).

Visiting the Chocolate Museum

The Museu de Xocolata is located in Barcelona’s El Born neighborhood and is very close to two of the city’s truly “must-see” attractions, the Palau de Música and the Picasso Museum. It’s open seven days a week, from 10 am to 7 pm (3 pm on Sunday), and as of July 2017, admission for adults is six euros. I would think this would be a great short visit for a young-ish family. The sculptures are very entertaining (I saw a group of five-year-olds laughing in delight at one of Barcelona’s football stars), and several are truly clever. If you want a slightly more highbrow or educational experience, the exhibits and sculptures also make a great jumping off point for discussions about trade and cultural exchange over the last 500 years. You’d probably be able to make a few good points before the kids picked up on the fact that your chocolate discussion was actually a covert history lesson.

What do you think? Does the Museu de Xocolata seem like your kind of place? And which of the chocolate sculptures would you want to run off with and snack on? Let me know in the comments section!

Comments (0)