I wanted to eat the air. I think that's a first for me.

National art and national identity: Visiting St. Petersburg’s Russian Museum

You know that quaint and vaguely demeaning phrase, “always a bridesmaid, never a bride?” Well, it sort of fits the subject of this post, St. Petersburg’s interesting but consistently upstaged Russian Museum. Try though it might, it will never be the star of the show.

It’s not the museum’s fault. It’s a nice place with a varied, if not knock-out, collection. The problem is that it’s in a rough neighborhood, and by that I mean that it has limelight-hogging neighbors. The incomparable Hermitage Museum is minutes away, and it doesn’t help that the awe-inspiring Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood is pretty much around the corner. Expecting visitors to ignore the siren song of the Hermitage in favor of the Russian Museum is a little like expecting kids to happily eat their veggies and ignore the macaroni & cheese.

The anti-Hermitage: Envisioning the Russian Museum

Like most things, the Russian Museum is best appreciated when looked at in its historical context (also don’t compare it to the Hermitage). As the name suggests, it is dedicated exclusively to Russian art (though, as many of the featured artists were not ethnic Russians, it might be more appropriate to refer to it as “art of the Russian imperial and soviet periods.” But that’s a serious mouthful and, as we’ll see, the thorny question of Russian nationality and culture is central to the museum’s story). In any case, the first thing to file away about the Russian Museum is that it was deliberately founded as something of an anti-Hermitage.

Originally called “The Russian Museum of His Imperial Majesty Alexander III,” it was founded in 1895 by Alexander’s son and heir, the ill-fated Nicholas II. Alexander had been, if not a connoisseur, than a definite champion of Russian art, just as he was a champion of most things Russian. In the early part of his reign, he had been appalled to discover the dearth of Russian art in the Hermitage collection, and instructed the museum’s directors to fix that–ASAP. For his part, the tsar made numerous donations from the imperial family’s own collection and encouraged members of the nobility to do the same.

Alexander must have kept up the pressure because, by the time of his death in November 1894, the state was in possession of enough Russian art to fill its own museum. Today the museum has more than 400,000 pieces, with everything from medieval Orthodox icons to obscure nineteenth century history paintings, to works by Russia’s greatest portraitists, Ilya Repin and Valentin Serov, and the modernist Wassily Kandinsky.

The collection is primarily housed in the the Mikhailovsky Palace, an old imperial property originally built for Catherine the Great’s grandson. But don’t go there expecting lavish interiors (you know, like those at the Hermitage…). The palace has a grand, yellow-colored neoclassical facade, but over the years, most of its ornate interior was stripped away. But a few grand rooms, impressive ceilings, and at least one blinding chandelier, do remain, allowing visitors a glimpse of the opulent surroundings Russia’s ruling class took for granted.

Going through the museum, a little background

The museum is very large, but so well-laid out it doesn’t seem overwhelming. Exhibits flow logically from one room to the next, and an audio guide provides helpful context. For me, the most impressive parts of the collection–by far–were the medieval icons and the numerous exhibits focused on the tumultuous era between 1860 and 1930. In a case of happy historical timing, that latter period of upheaval (the beginnings of industrialization, the growth of cities, an increasingly influential middle class, four wars, and three revolutions) coincided with the era in which Russian secular art really came into its own.

The Russian Museum’s collection includes a lot of sculpture. This one, by Mark Antokolsky, was my favorite. Don’t you think there is something both adorable and vaguely demonic in the baby’s determined gaze? It’s very “I will walk. And I then I will trample you.” Antokolsky, whom I’d not heard of before visiting St. Petersburg, was hugely prolific. You can see one of his other statues in one of the first “Wednesday” posts.

I enjoyed my visit and found the collection, as a whole, really interesting. But for the first 45 minutes or so, I was underwhelmed. Of course, I am not an art historian, just a highly opinionated regular historian, so this is just one non-expert’s opinion, but so much of the older stuff (with the exception of the magnificent medieval icons, which are in a category all their own) just seemed bland. Judging by the pictures I took (or rather, didn’t take), very little from the 1700s and early 1800s made much of an impression. I just couldn’t sense in the paintings any of the drama that I knew marked Russia’s past.

But if eighteenth century and early nineteenth-century Russian art wasn’t as “Russian” as I was expecting, that’s perhaps not so surprising. In that period the Russian elite was intoxicated by all things western, and this extended to the arts as well. According to Orlando Figes’ excellent history, Natasha’s Dance: A Cultural History of Russia, this fixation resulted in a contempt for and alienation from Russian culture, so much so that the elite lost touch with their “Russianness” in pursuit of western cosmopolitanism. I wonder if that contributed to the underwhelming mass of European-style history paintings and landscapes, so many of which just seem to lack the vigor and creativity of the later works on display.

But by the second quarter of the nineteenth century, and brought about in part by Russia’s struggle against Napoleonic France, the pendulum began to swing back, though actually turning back the clock proved impossible. Russian’s century-long entanglement with the west had made a mark, and for the next century (and arguably ever since) Russian artists grappled with rediscovering, reclaiming, and redefining Russian culture. The highlight of the museum’s collection are the galleries in which that tension is vividly displayed.

Russian culture, “Russianness,” and “Russification.”

This resurgence of “Russianness” in Russian high culture intersected nicely with the intense nationalism of Tsar Alexander III. But when Alexander instructed the Hermitage’s directors to acquire more Russian art, I don’t think it was the creative tensions between Russian culture and western influence that were on his mind.

Alexander was dedicated to the threefold governing principle of “Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality.” This meant the fashioning of a single Russian state with a strong tsar and a single strong, Russian, cultural identity. The immense linguistic, religious, and ethnic diversity of his empire was politically threatening and perhaps–considering his well-known anti-semitism–personally distasteful to him as well.

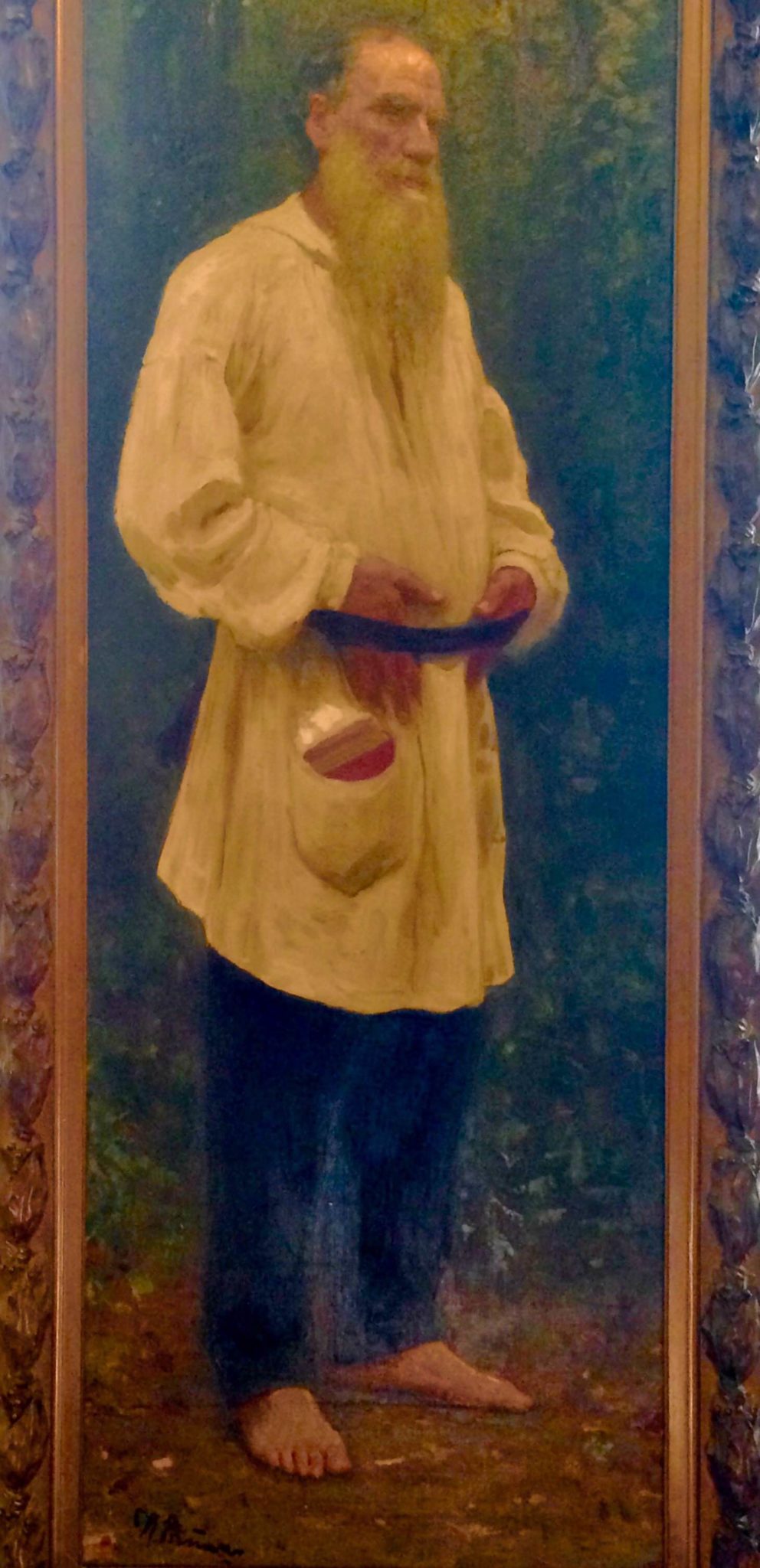

Ilya Repin’s 1901 portrait of Leo Tolstoy. Tolstoy’s peasant-style garb is reflective of the Russian creative class’ renewed focus on “authentic” Russian life. Like Tolstoy, many believed it had only survived in the “simple” and “uncomplicated” lives of the peasantry.

The propagation of Russian art and culture was a key part of this cultural assault. Celebrating Russian culture sounds benign enough, but it was of course meant to supplant and even eradicate other cultures. This plan of action, known as “Russification,” restricted and even outlawed various aspects of non-Russian cultures, and was deeply resented throughout the empire. In founding an entire museum of Russian art and naming it for his father, Alexander’s son, Nicholas II, both honored and endorsed his father’s nationalist ideals.

Tsar Alexander III, champion of Russian art and Russian everything else. [Wikimedia commons]

I’m not picking on the Russian Museum or trying to tar it with the nasty brush of nationalism, a sentiment that I believe has done far more harm in the world than good. (I will, however, pick on both Alexander III and Nicholas II, neither of whom was a person I’d want to drink vodka with.) There is nothing uniquely Russian about either nationalism or its relatively harmless expression in the form of a national museum (Smithsonian, anybody?).

But tastes are not developed, art is not acquired, and museums are not endowed in a vacuum. They belong to a particular historical moment and inevitably reflect its attitudes. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the impetus for the Russian collection came from the same tsar whose reign is most associated with Russian nationalism and its ugly cousin, Russification. And, at least to me, understanding the reason why the Russian Museum came into existence enhances, not diminishes, the experience of the museum itself.

Visiting the Russian Museum

The museum is open six days a week (closed Tuesdays) but daily hours vary. It’s always a good idea to check the website, www.rusmuseum.ru, before setting out. Admission is 350 rubles (about $6 as of May 2017), and the audio guide another 250 rubles.

There is a further 250 ruble “camera” fee, but I’m not sure how seriously that’s taken. I wasn’t asked to pay and nobody stopped me from taking pictures. Just be aware that it might come up. Also bear in mind that many of the galleries are lit dimly to protect especially delicate pieces, and that has a sad effect on photos.

Konstantin Makovsky, Portrait of Julia Makovskaya, the artist’s wife.

So, what do you think? Will the Russian Museum make it on to your St. Petersburg bucket list? And which famous Russian would you most like to have some vodka with? Let me know in the comments section!

Love this! I could talk about museums and national identity all day.

Thanks for the comment, Ellen! I definitely think you should talk about this stuff all day. I’ll have to write another museum post!