Building (literally) the Tudor dynasty: Lady Margaret Beaufort, Henry VII, and the Westminster Abbey Lady Chapel (Part I of III)

(I apparently had a great deal to say on this topic, so I decided to break up the post into smaller parts. Keep an eye out for parts II and III later in the week!)

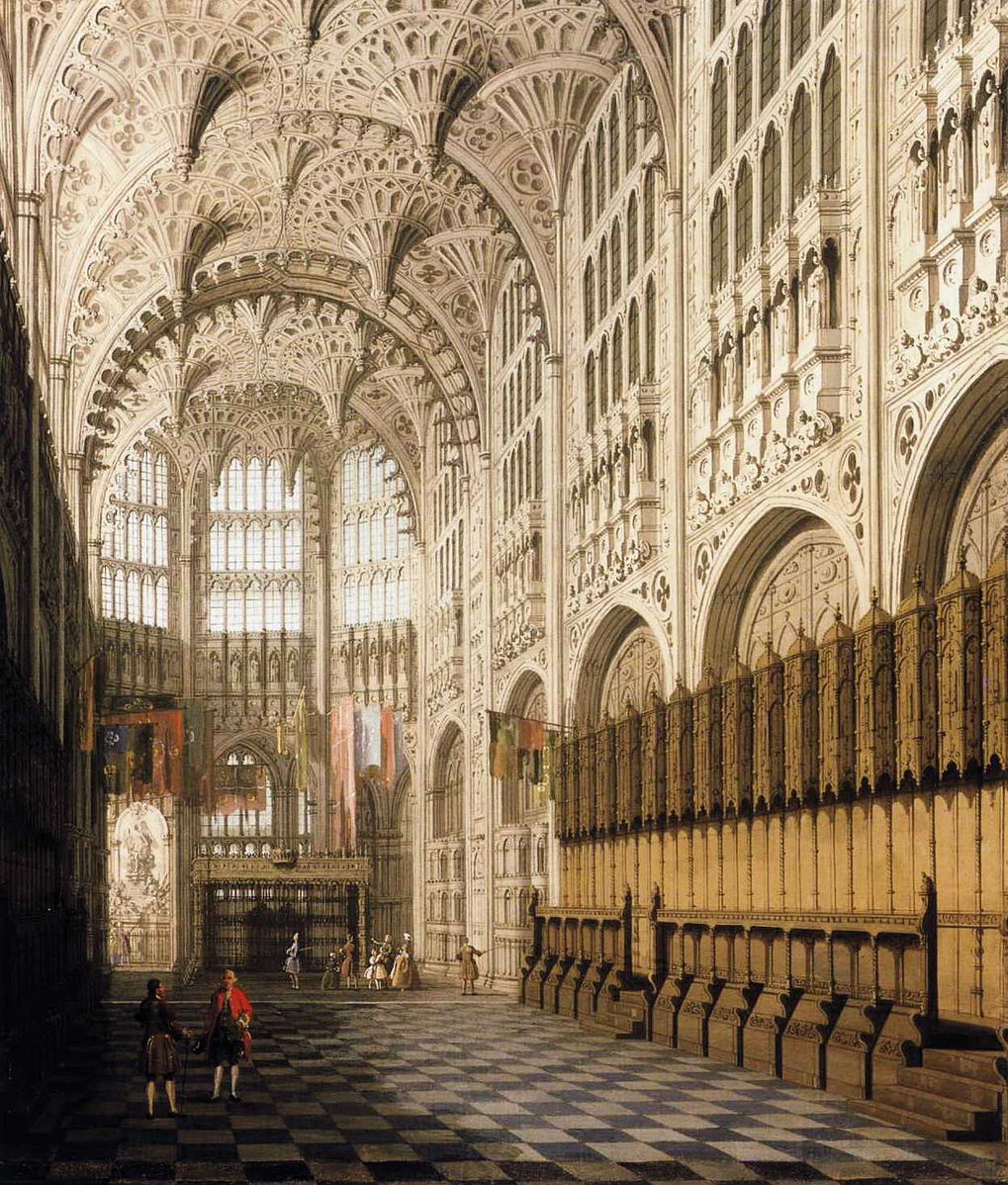

Westminster Abbey is one of my favorites of London’s “must-see” sites and Henry VII’s “Lady Chapel” (so-called because of its dedication to the Virgin Mary) is my favorite part of the Abbey. The Lady Chapel has three things guaranteed to make me happy: a fancy ceiling, plenty of stained glass, and royal associations galore. Four of the five Tudor monarchs are buried there, as are five of their Stuart successors (plus a few Hanoverians).

The Lady Chapel is also a masterpiece of royal propaganda, which, if my recent posts on the Bayeux Tapestry and the Painted Hall at the Old Royal Naval College are any indication, also makes me happy. When visiting the Abbey, make a beeline for the chapel and see the rest later. With any luck you’ll have a few moment to gaze in peaceful awe before everyone else catches up.

A view of the Lady Chapel, by the 18th century Venetian painter Canaletto. {PD-Art Wikimedia Commons}

In the chapel, not far from the tomb of Henry VII–the first Tudor king– lies the tomb and effigy of another, more obscure member of the dynasty–Henry’s mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby.

Lady Margaret Beaufort’s tomb in Westminster Abbey, sculpted by the Italian master Pietro Torrigiano. Be sure to note the exquisite detail on the two pillows. One features a portcullis design (the Beauforts’ heraldic symbol) and the other a Tudor rose. (Photography is not allowed in the Abbey, so, really, I have no idea how this ended up on my phone. But since it is there, it seemed selfish not to share it.)

Though never queen herself–indeed, she wasn’t even really royal–one can make the case that Margaret was the most important member of the family. Certainly she is up there with her son, as well as her more famous grandson, Henry VIII. And with the exception of her great-granddaughter, Elizabeth I, no woman contributed more to the power and legacy of the Tudor dynasty.

Lady Margaret Beaufort’s (virtually) impossible dream

In August 1485, Margaret’s son, Henry Tudor, defeated King Richard III (he of “a horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse” fame) at the Battle of Bosworth Field. Seizing the crown for himself, he was proclaimed King Henry VII. The victory was not Henry’s alone, but very much his mother’s as well. In the chaos of the Wars of the Roses (that thirty-year-long dynastic bloodbath that saw two branches of the English royal family–the Lancastrians and the Yorkists–tear each other to pieces in pursuit of the crown), Margaret saw a chance to put her son on the throne and used every weapon in her arsenal to get him there.

Now, when I say “chance,” what I mean is “tiny, laughable, this-woman-was-either-a-lunatic-or-a-psychic” type of chance. For a start, Henry’s place in the line of succession was super remote and, legally, quite iffy. Sure, when he defeated Richard, he was careful to dress up his victory as God’s verdict on his superior claim to the throne, but nobody actually bought that.

Edward Blair Leighton’s 1904 painting, “A little prince likely in time to bless a royal throne,” depicts Lady Margaret Beaufort holding aloft her young son, Henry. The title comes from a line in Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part III, when the tragic king points to little Henry and, prophesying his royal future, calls him, “England’s hope.” It’s a nice story, but I promise you it didn’t happen. {PD-Art Wikimedia Commons}

Henry came to the throne by virtue of bloodshed not bloodright. But proclaiming himself the lawful heir sounded a lot better than pointing out that he had just smashed in Richard’s skull and then plopped the muddy, blood-stained crown on his own head. Military success and the support of key members of the nobility had won the day, but this was not something you said out loud. Public relations is not an invention of the modern age.

The Beauforts’ legitimacy problem

Henry’s claim came from his mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, but it was both tainted and downright flimsy. The Beauforts were descended from a king, Edward III, but their descent was illegitimate, or at least it had begun that way. The founder of the line was John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, one of Edward III’s many sons. After fathering children with two wives, he produced four more with his mistress–these were the first Beauforts.

(Fun and entirely irrelevant fact: John of Gaunt’s mistress, Catherine Swynford–the matriarch of the Beaufort clan–was Geoffrey Chaucer’s sister-in-law.)

The Beaufort children were later legitimized, but an act of Parliament explicitly barred them, and their descendants, from any right to the throne. Unfortunately, in the 15th century, English law hadn’t yet decided how to treat the royal succession. Was it passed down from father to eldest (legitimate) son, like any other piece of property? Or was it outside the law and in the king’s gift, meaning could he “will” the throne to whomever he pleased?

In other words, it wasn’t clear if Parliament could bar John of Gaunt’s now-legitimate Beaufort descendants. If, if, the crown was a straightforward inheritance (which, indeed, is how the succession had more or less functioned since 1066) then the Beaufort family’s claim was handicapped only by their junior line of descent. If the senior line, meaning the descendants of Gaunt’s elder sons, died out, then the Beauforts would be entitled to claim its rights for themselves.

This is kind of question that lawyers and historians love (lawyers because they get to charge by the hour and historians because we’re weird). But it is not the kind of question you want having any kind of real life implications–especially in a world where issues of this sort were often resolved by bloodshed.

Of course, none of this would have mattered if the Lancastrian side of the family (John of Gaunt’s unquestionably legitimate descendants) had done a better job at that whole “being king” business. But they either were hampered by impossible circumstances (Henry IV), died too young (Henry V), or were incompetent and literally insane (Henry VI).

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster and founder of both the (royal) Lancastrian and (maybe/maybe not royal) Beaufort lines. If you’re wondering where you might have met Gaunt before, Shakespeare gives him the second-best speech in Richard II, the one that starts, “This royal throne of kings, this scepter’d isle/This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars/This other Eden, demi-paradise.” {PD-Art Wikimedia Commons}

(Confused by all the Henrys and Beauforts? I don’t blame you. Here’s a link to a well-designed family tree. http://www.luminarium.org/encyclopedia/houseoflancaster.htm)

The Lancastrian defeat

The Yorkist branch of the family (here’s a link to their family tree) eventually had enough. And since they had always thought they had the better claim anyway (don’t ask), turned to war as a means of settling the matter. A lot of bloodletting ensued, and by 1471 the Lancastrians had been so decimated that Margaret’s adolescent son, Henry Tudor, found himself its last male heir.

The 1471 Battle of Tewkesbury was one the most important battles of the War of the Roses. It was a great victory for the Yorkists and all but wiped out the Lancastrian line. This image, taken from the contemporary Histoire de la rentrée victorieuse du roi Edouard IV en son royaume d’Angleterre, depicts the beheading of Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, after the battle. His death left Lady Margaret the last of the Beauforts and her son Henry the unlikely heir to the Lancastrian claim to the throne. {PD-Art Wikimedia Commons}

Unfortunately, 1471 was a bad time to be a Lancastrian, and an even worse time to be a Lancastrian heir. The Yorkist claimant, King Edward IV, had won the day. The war, it seemed, was finally over. But Henry Tudor was a loose end Edward could not afford to ignore. Despite his young age (he was 14 in 1471), Henry was an attractive rallying point for Yorkist enemies and Lancastrian diehards (who were not necessarily different groups of people; among the nobility, loyalties shifted frequently).

Margaret quickly sent her son out of the country for his own protection. She wouldn’t see him again for another fourteen years. In the meantime, she herself would have to cope with the problem of having Lancastrian blood in a Yorkist world.

Coming up! Margaret navigates the new political realities and plots to topple the Yorkist dynasty.

So if the “scepter’d isle” speech is the second-best in Richard II, which is the best? The “sad stories of the death of kings” speech? Maybe you address this in parts two or three, whence I will soon re-sojourn. My own favorite from Richard II is Norfolk lamenting over his exile.

I didn’t know that John of Gaunt’s mistress was Chaucer’s sister-in-law! Chaucer served in Richard II’s court in some capacity, right?